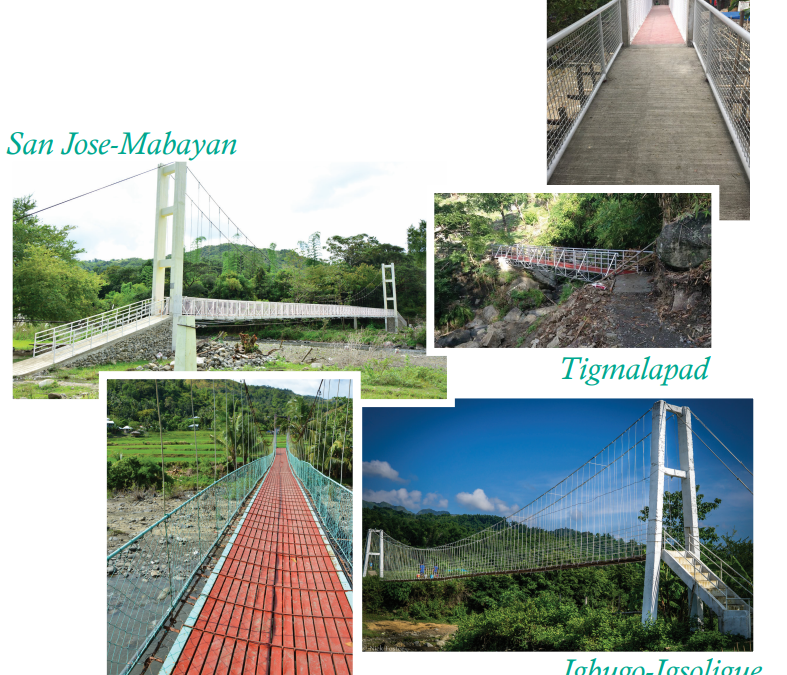

MIAG-AO CHURCH – a Fortress of the Spanish Empire?

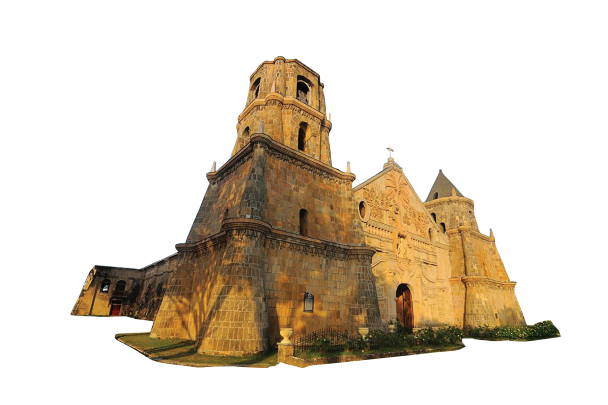

Fig. 1 Miagao Church. Photo by Ronald Medina

Rumors, if passed along often enough, may turn into urban legends; and, sometimes become accepted as a historical fact. Just give it enough time to circulate around for over a generation or two. Most towns and cities have their own urban legends and the usual ‘mis-encounters’ with historical accuracy. Such is the case even for the seaside town of Miag-ao (Iloilo) which is entering its 300th Foundation Day in February, 2016. I was excited to read the 1997 book, by Rene B. Javellana entitled ‘Fortress of Empire’ that describes the history and function of the various fortifications built during the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines. The book is out of print and taking such a long time to get to the National Bookstore in Iloilo City. In the meantime, a friend managed to borrow a copy for me from the library of Central Philippine University.

Why am I so interested?

The Miag-ao Church is often referred to as the Miagao Fortress Church, but I could not see what part of the Church made it a fortress. I have seen many fortresses and churches in my travels around the world—Spain, Italy, France (plus a dozen other countries in Europe), Latin America, United States, all over Asia and even Africa. In each of the more than 60 countries I have visited, I made it a point to visit historic fortifications. It became sort of a hobby I suppose, an extension of my boyhood interest during my formative years in a military family and many years later with the US Army.

Monsignor Claudio S. Sale, the former parish priest of Miag-ao for 17 years, received his Master in Archaeology in Spain. He oversaw the restorations of the Church and was the Parish Priest when Miag-ao Church became dedicated as a World Heritage Church by UNESCO. Recently, we interviewed Monsignor Sale about the church. Monsignor Sale, on the questions of the Church being a fortress had this to say:

Arjun P. Palmos: Monsignor, can you please give us an overall view of Miag-ao Church? Monsignor: At the outset, church is not just about the structure. The Church is actually about the people of God. Miag-ao Church is over 200 years old. It celebrated its bicentennial in the year 1997. One of the baroque churches in the Philippines, yes, but Miag-ao Church is not a fortress church. It is a misconception to call Miag-ao Church as fortress church although it may look like one.

APP: Why is that so Monsignor?

Monsignor: The impression may have arisen because of the huge buttresses of the Church. If you take a look at it, the Church has 7 stone buttresses on each side. These serve as “Contra Puertes” of the church meaning, these massive buttresses were constructed and designed to reinforce and withstand earthquakes and typhoons, but not for any military purpose. So, it is wrong to claim that Miag-ao church is a fortress church.

Having seen photographs of Spanish era fortifications in Javellana’s book and my own old photos of fortresses and churches around the world, I tend to agree with Monsignor Sale that the ‘fortress’ designation is not correct. Let me tell you why. First, those of us who are not familiar with fortress architecture, the buttresses on each side of the church might easily be mistaken as a defensive structure. But churches with high walls make use of buttresses to strengthen the structure against earthquakes rather than as a defensive design.

The definition of buttresses in Wikipedia is as follows: “The purpose of any buttress is to resist the lateral forces pushing a wall outwards by redirecting them to the ground. The defining characteristic of a flying buttress is that the buttress is not in contact with the wall like a traditional buttress; lateral forces are transmitted across an intervening space between the wall and the buttress.”

The definition of buttresses in Wikipedia is as follows: “The purpose of any buttress is to resist the lateral forces pushing a wall outwards by redirecting them to the ground. The defining characteristic of a flying buttress is that the buttress is not in contact with the wall like a traditional buttress; lateral forces are transmitted across an intervening space between the wall and the buttress.”

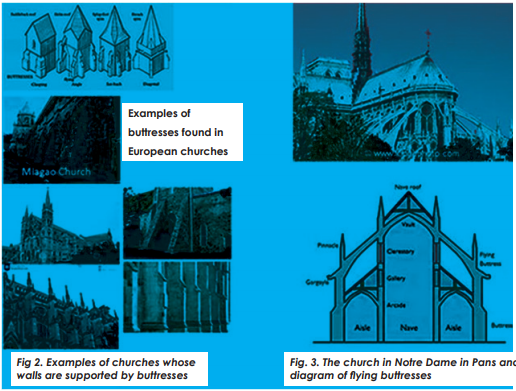

Figure 2 shows the typical buttresses in European churches compared to the buttresses on each side of Miag-ao Church. Among the most elegant of churches built with a modified version of the standard buttresses, also called flying buttresses, is Notre Dame in Paris seen in Fig 3. All of these churches did not serve as fortresses in the conventional sense of the word.

Second, buttresses are not used in military fortifications on the outside defensive walls because they hinder the view of the defenders and become places where the attackers can hide. The defenders on the towers and ramparts would not be able to target all of the attacking forces once they are close to the walls.

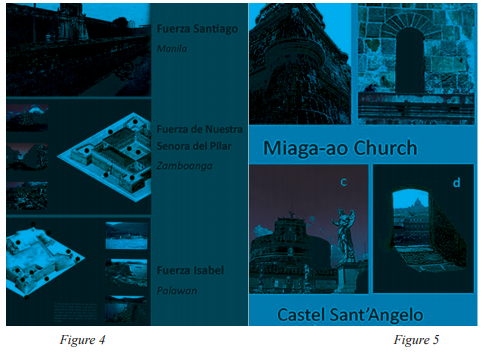

You may say that perhaps this is true only for European churches and fortification but not with Spanish era colonial fortifications. So, let me show you some examples from Javellana’s book on Spanish fortifications in the Philippines (Fig. 4). Here you can see the plain walls of the fortresses, with no buttresses so that the defenders can have a clear sight of the approaching enemy at all angles.

How about the openings on each of the two towers of Miag-ao? Are they not openings for defending soldiers to fire down on the attackers?

Not really. It is my view that they are merely windows for ventilation for each of level of the tower.

Fig. 5 shows close-up photos of the window of Miagao Church tower (a, b).

The opening is straight-cut on all sides and quite narrow. I had been up there a few times in the past and it would have been impossible for more than one person to use that opening to fire a musket or shoot arrows down below. And just one opening at each side of the tower on the second level is far too few to be an effective defense. It does not make sense; a totally inadequate design for a defensive position. In contrast, Fig. 5 d is an example of a typical firing position from the opening of the wall of Castel Sant’Angelo (Fig. 5c) in Rome. Note that the window (also called arrow slit) was cut at an angle from all sides, enabling 2 to 3 soldiers to fire at the enemy from a wider window. This is typical defense architecture that persisted through the centuries.

An example of a true FORTRESS CHURCH in the Philippines can be found in the island of Capul located in the narrow strait between Samar and the Bicol Peninsula used by the ships of the Galleon Trade.The strategic location required the construction of a bastion fort as part of the church dedicated to San Ignacio Loyola.

Was there ever a time when there is a recorded attack of the Moros on the Miag-ao Church after it was built?

The Church was completed in 1797. Although the Moro wars persisted until the 1850’s, those battles after 1797 were fought elsewhere—Mindoro, Samar, Cebu, Zamboanga, Cavite, etc. There were no records that Miag-ao Church was attacked at any time after it was built. The Moro invasion celebrated in Salakayan Festival of Miag-ao occurred in 1754, more than 30 years before the church was built. One may also argue that Miag-ao Church is a refuge, where people flock during attacks or calamities and therefore can be regarded as a fortress. Yes, if one likes to stretch the meaning of fortresses as walled refuge. If one accepts that argument, then the Miag-ao Municipal Hall and Cultural Hall should have a fortress designation as well because Miagawanons go to both places for refuge during typhoons. In fact, in times of recent typhoons, Miag-ao Church was always closed to the public and the people flocked to the Cultural Hall instead.

If this argument is accepted for the Church to be a fortress, then to be fair, should we then call the Cultural Hall as The Judge Ramon Britanico Fortress Hall?

Although calling our Miag-ao Church as a Fortress Church does sound more dramatic, it is totally inaccurate. At times, even Paoay Church is also referred to as a fortress church and likely also not true.

Here is Wikipedia entry about Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte: Paoay church is the Philippines’ primary example of an earthquake baroque architecture dubbed by Alicia Coseteng, “an interpretation of the European Baroque adapted to the seismic condition of the country through the use of enormous buttresses on the sides and back of the building. The adaptive reuse of baroque style against earthquake is developed since many destructive earthquakes destroyed earlier churches in the country. Javanese architecture reminiscent of Borobudur of Java can also be seen on the church walls and facade.”

Buttresses

The most striking feature of Paoay Church is the 24 huge buttresses of about 1.67 metres (5.5 ft) thick at the sides and back of the church building. Extending from the exterior walls, it was conceived to be a solution to possible destruction of the building due to earthquakes. Its stair-like buttresses (known as step buttresses) at the sides of the church is possibly for easy access of the roof. Someone simply made up the ‘Fortress’ part; no one disagreed and becomes an accepted fact–The beginnings of the urban legend.

You may say, “Why bother with this?” The concept of the new Philippine educational system is to promote local language, tradition and history in the early stages of education before studying history and traditions in the national level. It preserves the local language and

makes the new students appreciate local history. But, history, especially local ones, must be accurate as best as possible. Preserving urban legends is not likely the wish of educators, though it is certainly good for tourism. The Church is the center of any Philippine town and it is important that what we tell other visitors is as accurate as possible.

The Miag-ao Church is a grand structure and certainly a major tourist attraction. Hopefully in the years to come, the Church tourism will translate into creating an economic boom for our town. And, as we wait for that time, we need to start upgrading our historical knowledge about the Church and about many other unique places in Miag-ao.

References: 1. Javellana Rene B. (1997). Fortress of Empire: Spanish Colonial Fortifications of the Philippines 1565-1898. Bookmark Inc, publisher, pp 209.

By: Jonathan R. Matias

Sulu Garden, Miag-ao, Iloilo

www.sulugarden.com

The new church was built for a variety of uses. Primarily erected as a place of worship, it was also a fortress where parishoners could evacuate for protection from inavasions.

The new church was built for a variety of uses. Primarily erected as a place of worship, it was also a fortress where parishoners could evacuate for protection from inavasions.